Shelter’s prescription to end the housing emergency

Published: by Rose Grayston

Building social housing is the only effective, long-term cure for the housing crisis. That’s why last week we joined with the National Housing Federation, Crisis, the Chartered Institute for Housing and the Campaign to Protect Rural England to fight for the homes we need: a funded programme of 150,000 social and affordable homes a year. From this Saturday, Shelter will be taking to the streets to ask you to add your support to our campaign, starting with our first street stall at Mill Hill Broadway. Together, our voice is louder.

Higher house prices are forcing more and more people into the insecure and often unaffordable private rented sector. 1.1 million people are now on the waiting list for social housing, while many more have simply given up trying to access a shrinking stock of social homes. The only effective long-term solution to the housing crisis? Building social housing – yet last year England built just 6,500 homes for social rent.

This just isn’t good enough, but we can do better. Reporting in January, Shelter’s commission into the future of social housing set out a vision calling for a return to post-war levels of social housebuilding. In the three and a half decades after the end of the Second World War, councils and housing associations built 4.4 million social homes at an average rate of 126,000 a year. This level of building was kept up through post-war reconstruction and despite three recessions in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Today we face an even greater challenge to provide safe, secure, affordable homes for all. It’s an ambitious vision and it will take commitment from the new government to get there. But together we can do it – and here’s how.

Shelter’s prescription

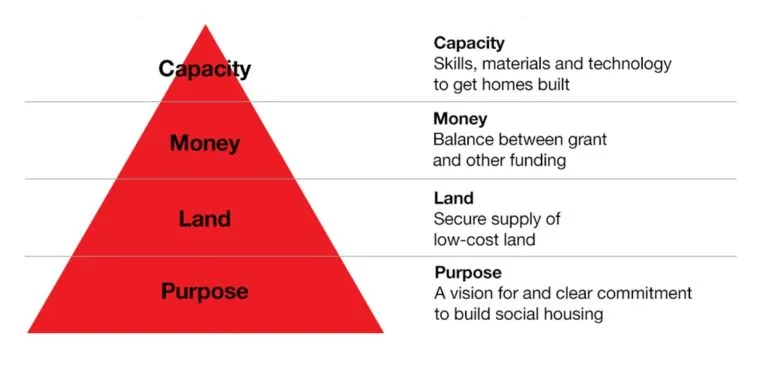

There are four key ingredients needed to build social housing. Together, these ingredients have been the foundations of every period of successful social housebuilding in England’s history:

Purpose

Social housing has meant many different things to different people over the years. Homes Fit For Heroes tackled squalor and offered the promise of a better life after World War I, while post-World War II governments used social housing to expand overall supply and replace stock lost to war or slum clearance.

In every case, the support of central government, with a clear vision for what social housing should achieve and a commitment to build, has been needed to get the other ingredients in place. Today, we need a renewed commitment from the next government to:

- change the law and the planning system to guarantee a supply of affordable land

- provide the grant funding needed to enable truly affordable social rent homes to be built

- support housebuilders, councils and those who produce the raw materials for building homes to innovate and increase their capacity

Land

Land is extremely expensive – especially in the places where new homes are needed most. The total value of residential land in the UK has exploded in recent years, rising by 583% from 1995–2017. Little wonder that forthcoming Shelter research with the Local Government Association shows the high cost of land is the single biggest barrier councils face in getting social housing built. Last week, Savills research with housing associations revealed access to land remains their biggest barrier to building more of it.

But things weren’t always this way. Social housing providers in the immediate post-war period benefited from legislation which allowed them to access land at a lower cost. As Shelter’s Grounds for Change essay collection argues, the new government must reform the Land Compensation Act 1961 to provide a secure supply of affordable land on which a new generation of truly affordable housing can be built.

Money

The lack of a sustainable and adequate source of funding is at the heart of our current inability to deliver social homes. While at the beginning of the 1990s grants covered around three-quarters of the costs of building new homes, this fell to 39% after the financial crash. The 2011–15 Affordable Homes Programme gave no grant at all to social housing, and the current Shared Ownership and Affordable Homes Programme for 2016–21 was only expanded to provide some funding for social housing in June 2018.

This has had enormous consequences for social housing supply because grant rates have simply been too low for many prospective social housing schemes to go ahead. That’s why Shelter has joined with allies across the housing sector to call for £12.8 billion of annual investment in social rent and other types of affordable homes. This would bring the share of building costs covered back up to 44%, kick-starting a new generation of social housebuilding.

Capacity

Finally, though no less importantly, social housebuilding needs development capacity to actually get the homes built – that is the people, materials and technology to turn these grand visions into reality. New players, both public and private, will be needed to replace the capacity that was lost when hundreds of SME builders went bust after the last financial crash, and local authority planning departments must be properly resourced. Modern methods of construction and other new approaches are needed to move housebuilding in England from a model of low market supply to one of significant social and market supply.

We should not underestimate the scale of this challenge. But nor should we assume that development capacity for social housebuilding follows the same rules that constrain capacity in market housebuilding. In fact, the countercyclical demand generated by a programme of social housing would support an expansion of capacity – and with it a significant number of well-paid jobs.

Join 60,000 other supporters. Ask the government to fill out Shelter’s prescription by signing our petition to #BuildSocialHousing. Together, we can make the government listen.