Why town planners need to be more like Michelangelo

Published: by Rose Grayston

A new report from the Raynsford Review explains why the planning system has worsened over the past hundred years and that, to fix it, we need to start talking about homes and not units again.

Planning is not boring, honestly. It’s critically important. It’s not about S106 and CIL, but rather affordable housing, and how communities function. And it’s at a crossroads right now, as the government is currently reviewing national planning laws.

It’s therefore timely that a new report by the Royal Town Planning Institute wants to remind us what good planning looks like.[1]

As one of the many pithy passages in the report puts it: we have to decide whether planning is “a form of land licensing…or the much more complex and creative practice of shaping places with people to achieve sustainable development.” In other words, is planning more like painting by numbers, or painting the Sistine Chapel?

The RTPI frames the answer to this around three further (albethey quite rhetorical) questions:

- should we leave the decisions about the future organisation of communities solely to the market and private property rights?

- should decision-making be taken out of democratic control?

- and do we have too much planning or too little?

Leave it to the market?

Planning is primarily about how we use land. So, this question could really be rephrased as: “should we leave the decisions about how to best use land solely to the market?”

Going over the history of housing and planning – which the report does very neatly – the answer would have to be no.

The postwar consensus to build more homes led to important reforms of compulsory purchase laws, allowing land to be bought more cheaply. This left far less for landowners but resulted in the highest consistent level of house-building in the nation’s history.

This system was refined in the 1950s to give larger returns to landowners – while still keeping land prices low enough for councils and development corporations to be able to build hundreds of thousands of affordable and popular new homes. But dogged lobbying overturned this and the 1960s saw a return to a system of high land costs, with higher returns for landowners, but fewer community benefits and affordable homes.

These changes clearly chipped away at the founding principles of the postwar planning system: that land is a public good and so should be used in a regulated way to create environments which promote the health and happiness of society. Our current model of development does not adhere to these ideas.

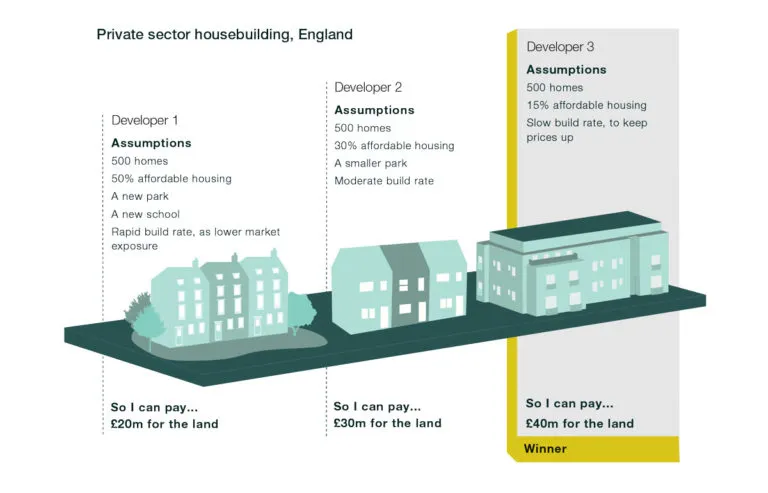

As our own New Civic Housebuilding report showed last year, high land costs and intense competition in the land market instead triggers a race to the bottom where perversely, the developer who plans to offer the least to the community in terms of affordable housing and infrastructure, will be able to offer the best price to the landowner, and so gets the privilege of the land.

Planning for people

Despite this, the RTPI claims there has been another, more subtle, regression in planning over the years: it has stopped thinking about people.

From the mid-1960s, decades of short-sighted government reviews and tweaks eroded the holistic old consensus, giving way to a new, more fragmented system. Significantly, it started to give new weight to case law, allowing for ambiguities and confusion to fester, while also moving power from planners to lawyers.

This has continued in recent years according to the RTPI, with reviews like The Barker Reviews of 2004 and 2006 focusing too narrowly on units alone and the needs of those delivering said units.

As the report puts it: “If the core ‘exam question’ of previous reviews had been how the system should operate democratically for a range of users, the new exam question was focused on how the system should work for the promoters of development.”

The main reason for this change is the decline in the political consensus over what planning is for.

Too much planning or too little?

So, how do we correct this? More planning? Surely not! Well yes, actually, just more decent planning.

As the report puts it: ‘Ironically, while deregulation has made planning less effective, the legal framework that underpins it has become more complex and confused’. The result is an adversarial, excessively flexible system which fails to set down clear and consistent expectations of development.

Take the Section 106 system. Introduced as a simpler way of extracting community benefits from land values flowing to developers, the viability system has mutated it into a gruesome swamp monster of planning. Years of case law have led to a confused legal tangle, stalling development, overwhelming some councils and slashing affordable housing numbers.

And it’s the anti-red tape zealots to blame, who’ve become the thing they set out to destroy.

We need a stronger planning system

Conveniently, the government’s view on all this will be made clear soon when the new National Planning Policy Framework is published in July. The draft showed an unfortunate continuity with the failings above. Viability, for example, has been given a more central role in deciding affordable housing, and local authorities have seen their powers further diluted.

Instead of trying to cut corners, we need a clearer, stronger planning system. We must ensure that local authorities have the ability to set and enforce targets for affordable housing and community infrastructure, as well as empowering development corporations to go away and build the big, bold new towns we need once again.

Without that, we’ll just have to live with the swamp monster, and continue to leave the Michelangelos of planning out in the cold.

[1] The report presents the interim findings of the RTPI’s review of the planning system. The full report is due out later in the year. http://offlinehbpl.hbpl.co.uk/NewsAttachments/RLP/RRinterimreport.pdf