Selective licensing in Newham: a local scheme of national significance

Published: by John Bibby

When Newham Council introduced the first borough-wide licensing scheme in 2013, it looked like a novel way to improve their booming private rented sector.

While licensing powers were originally introduced in the mid-2000s as a targeted tool to tackle anti-social behaviour, Newham’s ambition was much bigger. They adopted a borough wide scheme to integrate licensing with their other environmental health powers and crack down on rogue landlords and poor conditions too.

It’s an approach that has got results. In the last four years they have prosecuted more bad landlords than any other London borough and issued more than 2000 improvement notices to tackle poor conditions.

But a government change in 2015 means Newham’s plan to continue their scheme for a further five years will require the approval of the Secretary of State next year, which no other council has yet successfully got.

So their pioneering position has national implications. It will perhaps provide the best indication of whether the Secretary of State will back councils who want to improve private renting conditions.

We think they should. There are strong arguments for more coordination and a fuller review of licensing over the long term. But for private renters in Newham, this novel use of powers is helping to protect them from rogue landlords today.

The Newham approach to selective licensing

Some essential background: there are three tiers of property licensing in England:

- Mandatory licensing, which applies to all large Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs), wherever they are in the country

- Additional licensing, which applies to smaller HMOs, where the council adopts a scheme

- Selective licensing, which applies to other non-HMO private rented properties, where the council adopts a scheme.

All three of these tiers of licensing are in operation across the whole of Newham and underpin their approach.

Newham’s central assumption is that any landlord who is willing to flout the law when it comes to licensing is unlikely to hold a deep respect for their tenants’ legal rights – or the condition and safety of the property or getting planning permission or even paying their tax.

Find those who fail to get the right licence, and you can weed out those who aren’t meeting their wider obligations as landlords.

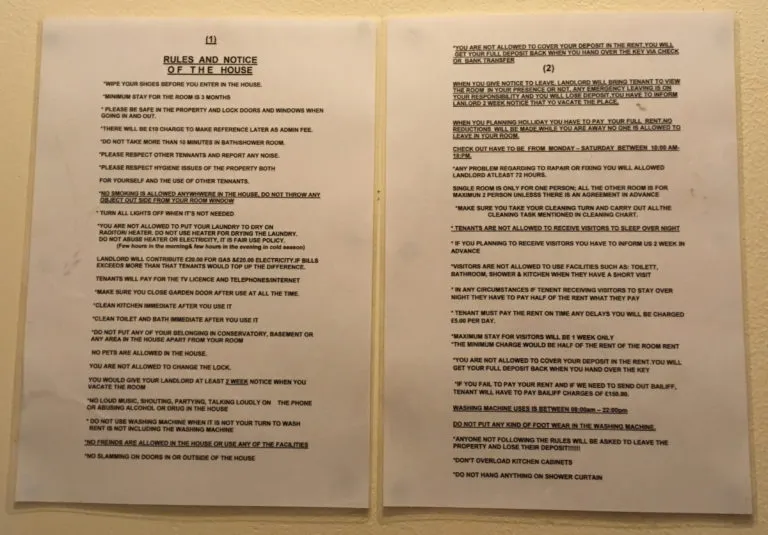

We saw this at work when we recently shadowed an operation by the council. The first property we visited was plastered with ‘rules of the house’ that, for example, included a threat to withhold tenants’ deposit if they let guests use the toilet. If the landlord followed through on this threat, it could be theft.

These rules were pinned to the wall in a Newham property where the landlord were breaching the terms of their licence

Sure enough, the landlord there had a licence for fewer than five tenants. But at least twelve were living there across three floors, including one family with a small child, and the possibility of someone else living in an outbuilding in the garden.

Newham says using licensing in this way has helped to completely revolutionise their ability to take on rogue landlords and tackle bad conditions in their rapidly growing private rented sector.

With all the data that the council has at its fingertips, finding landlords with the wrong licence is relatively easy and often bears results. The intelligence that they gather can then also be used to tip-off their conventional environmental health enforcement, which acting alone can be painfully slow to get results.

With the proportion of private rented housing in the borough having almost doubled from 23% to 45% between 2009 and 2016, and council budgets under extraordinary pressure, you can understand this imperative to deliver results speedily.

Extending Newham’s selective licensing scheme

While Newham’s approach has clearly got results and the council says it has strong local support, not everyone has been happy with borough-wide licensing. Some landlords and letting agents have been unhappy with having to pay the licensing fee that covers the administration of the scheme and allows the council to check, for example, whether landlords applying for a licence are fit and proper persons.

In 2015, the then housing minister responded to these complaints by announcing that any new schemes covering more than 20% of a borough’s properties or area would need to be signed off by the Secretary of State.

The changes were widely interpreted as meaning the government just wanted to put a stop to borough-wide selective licensing. Newham itself will be obliged to get Secretary of State sign off to renew the scheme next year.

The indications of success look poor. For example:

- Following the rejection of Redbridge Council’s proposed scheme by the last Secretary of State, no borough-wide selective licensing scheme has been given the government’s OK

- When the current housing minister’s local council proposed a selective licensing scheme in 2014, he became a vocal critic

- And the government’s consultation to extend mandatory HMO licensing last year may provide additional political cover to bear down on the use of selective schemes.

An application of national significance

So Newham’s application to extend their scheme has significance beyond the borough.

Their use of licensing in this way has helped turn around enforcement in the borough and won them plaudits.

They can make a strong case to government for their pragmatic approach. If that doesn’t happen, the kibosh has well and truly been put on use of borough-wide licensing as a way of tackling rogue landlords.

We think that would be a very bad thing.

Licensing at present is not perfect. For example, the variety of schemes has led to a patchwork of different enforcement regimes, which can be confusing for both landlords and tenants. (The irony of the requirement to get Secretary of State sign-off for schemes covering more than 20% of an area is that it has pushed councils to adopt even smaller schemes and an even more fragmented patchwork.)

But the way to tackle this is through greater coordination at a combined authority or county level, just as the Mayor of London has said he would like to in the capital.

Under the existing law, with its resource and time intensive conventional approach to environmental health enforcement, these are pragmatic powers that allow cash strapped councils to get results quickly.

And at a time when the private rented sector is growing at an unprecedented rate, it’s vitally important that places like Newham are able to use every weapon against rogue landlords in their arsenal.