Don’t be fooled by the campaign to axe stamp duty

Published: by Rose Grayston

Ahead of the Autumn Budget, the Daily Telegraph is leading a fresh charge against stamp duty land tax – a levy on property purchases which taxes the average buyer lightly, but hits buyers of £1 million+ mansions, second homes, and buy-to-let properties harder. Now MP Jacob Rees-Mogg has put cutting stamp duty ‘as a matter of urgency’ at the centre of his prescription for the Conservative Party.

A spate of articles have dubbed stamp duty ‘a tax on mobility and aspiration’ and ‘a tax on freedom and happiness’. The Telegraph concludes that it is holding back Britain’s housing market, pushing down transactions and the supply of new homes, stopping older homeowners from downsizing and growing families from upsizing. The paper quotes new research from the LSE and the VATT Institute to back up its claims.

We at Shelter think the tax is shouldering the blame for the country’s housing woes unfairly. It is certainly true that the UK’s housing market does a poor job of meeting housing needs, with low rates of moving amongst homeowners, low supply of new homes and significant under-occupation of the homes we do have. But how much of this is really driven by stamp duty?

The LSE and VATT Institute researchers (who were actually assessing the old, regressive system of stamp duty abolished in 2014 rather than the one we have today) found that even if we scrapped the charge entirely, households in the UK would still move significantly less than their US counterparts. Stamp duty reforms in 2014 actually reduced charges for 98% of home buyers, yet transactions remain stubbornly low – 400,000 home sales per year below pre-recession levels.

So what is going on?

What is stopping people from buying and moving?

Compared to all the other costs of buying a home, the truth is stamp duty just isn’t very important. Stamp duty is paid in ‘slices’, based on the value of the property: nothing on the first £125,000, then 2% up to £250,000, then 5% up to £925,000, then 10% and so on. So for the average home, valued at £223,000, just under £2,000 in stamp duty is due. Most homeowners will pay more in estate agents fees.

Compare this to the average first-time buyer deposit of £33,000, rising to £107,000 in London, and it’s clear that the high house prices are what really stop people from buying homes – not stamp duty.

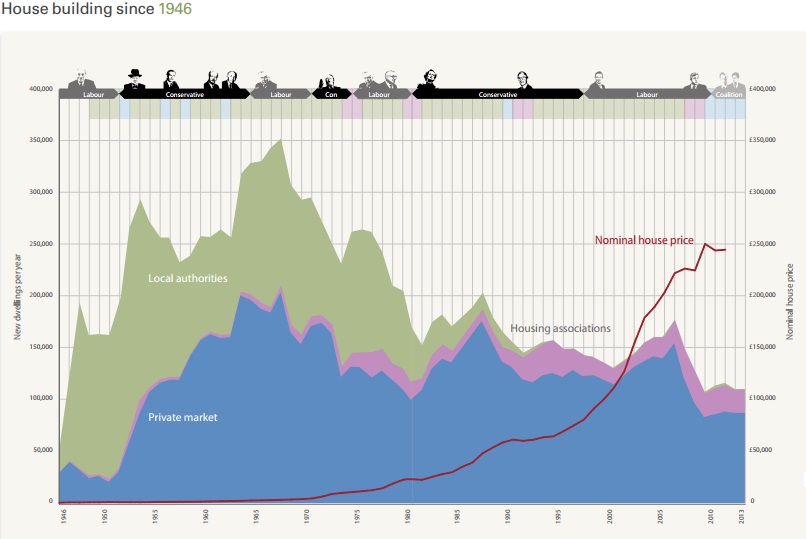

We simply haven’t been building enough homes, for decades. And the homes we have been building have been far too expensive to meet ordinary people’s need for housing. The impact on house prices is clear to see.

This crisis in the availability of homes that are affordable to people on ordinary incomes affects those looking to upsize or downsize as well as first-time buyers. Between 2011 and 2016, house prices in England increased 10 times as fast as wages. This means those with a foot on the ladder often find it impossible to save or borrow enough for a move up, as recent research from the Council of Mortgage Lenders demonstrates.

On the other side, most older people with spare bedrooms do not live in the £1 million+ mansions that fall into higher stamp duty tax brackets, but in average priced homes. They have very little financial incentive to downsize, even without stamp duty. House prices are now so eye-wateringly high across the board that moving from, say, a three bedroom to a two bedroom home fails to release enough equity to make the move worthwhile. Many older people also have specific needs for housing that is easy to maintain or has level access, supply of which has suffered along with the UK’s poor track record on housebuilding overall. It is unsurprising, then, that the leading reason over 55s do not go through with a planned move is a lack of suitable properties.

Would scrapping stamp duty help?

The irony of the campaign to scrap or drastically cut stamp duty is that it wouldn’t even make housing cheaper to buy. House prices are driven by what people are willing to pay, so any money not spent on stamp duty means more to spend on the home itself. In a system of highly restricted housing supply, that means more money chasing the same number of homes, inevitably pushing up house prices. Since the housing market crashed in 2007, government and Bank of England policies have done exactly this: Help to Buy, quantitative easing, inheritance tax cuts and, indeed, stamp duty cuts from 2014 have all served to shore up house prices, freezing more people out of home ownership while limiting choice for those already in the club in the ways outlined above.

Overall, the impact of stamp duty on the housing market is extremely limited, except in one important respect: it taxes the overconsumption of housing, as those buying a second or additional home will pay 3% more on each stamp duty ‘slice’ compared to people buying a home to live in themselves. In doing so, stamp duty has a small dampening effect on the demand for housing, giving a competitive edge to those buying to occupy.

Change is desperately needed to tackle the housing crisis and make sure everyone has an affordable, secure place to call home. From speeding up the rate at which we are building homes, to making sure Housing Benefit covers rents, to driving up security for private renters, there’s plenty of work to do. Further reforms to stamp duty are just not a priority given the scale of these challenges. The campaign to axe stamp duty might be dressed up as a civic-minded crusade to help your nan downsize, but the only real winners would be buy-to-let landlords and those buying holiday homes and £1 million+ mansions.