Temporary accommodation: the new social housing?

Published: by Hannah Rich

Temporary accommodation is the name given to the accommodation that is offered to people who seek help from their council because they are homeless. Councils have a legal duty to accommodate most homeless families until a suitable settled home is offered.1

New government statistics tell us how many households are living in temporary accommodation and how much councils spend on this insecure homeless accommodation.

Almost 100,000 households are living in temporary accommodation

At the end of September 2021, there were 96,060 households living in temporary accommodation in England, including over 120,000 children. This means that almost 100,000 households – equivalent to a town the size of Oldham – are living in insecure and often cramped, poor-quality accommodation.

More than a quarter (27%) of these households are accommodated outside the local authority area they previously lived in because councils can’t find suitable accommodation locally. This can lead to long, tiring journeys to school and work and families becoming isolated from support networks.

The number of households living in temporary accommodation is now approaching levels last seen in the mid-2000s. In the last 10 years alone it has increased by 96%.

Temporary accommodation costs over a billion pounds a year

As well as being insecure and unsuitable, temporary accommodation is also hugely costly. New figures show that councils in England spent £1.45 billion on the provision of temporary accommodation between April 2020 and March 2021.2 This cost is covered in part by housing benefit and people having to top up their rent.

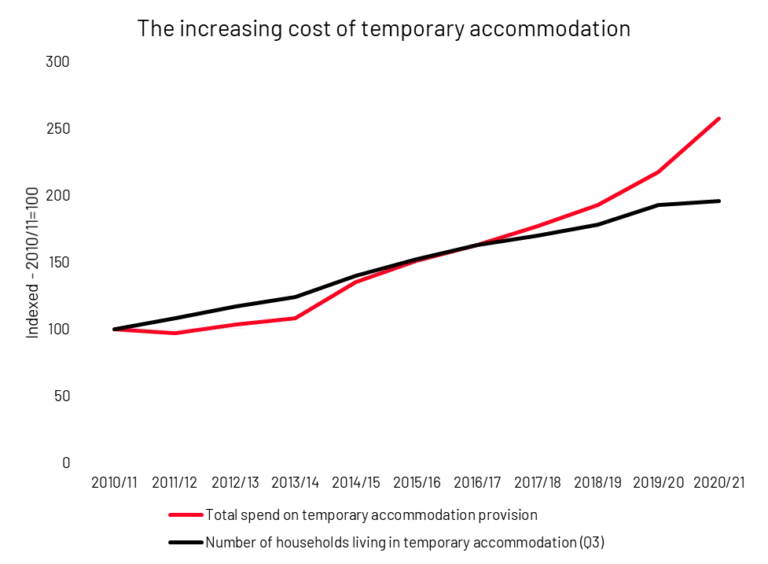

The cost of providing temporary accommodation has increased by 18% in the last year alone and more than doubled (increased by 157%) in the last 10 years. This means that the cost of temporary accommodation has increased at a greater rate than the number of people living in temporary accommodation.

Of course, housing costs are likely to increase over time. However, this disproportionate increase in the cost of temporary accommodation can be explained, at least in part, by the lucrative market that has emerged in the last few years.

A graph showing the increasing cost of temporary accommodation

Most of this money goes to private providers

Our recent Cashing In report showed that councils procure most of their temporary accommodation from for-profit private providers, who are often unregulated. This hasn’t changed.

The majority of the £1.45 billion goes to private providers of temporary accommodation. At least £1.16 billion (80%) was spent on accommodation leased by councils and social landlords from private letting agents, landlords or companies. And this doesn’t even include temporary accommodation provided directly by private landlords.3

More than a third (38%) of this money was spent on emergency homeless B&Bs – considered some of the least suitable places for families and children to live. Councils in England spent £444 million on this type of accommodation between April 2020 and March 2021.

Almost a fifth (18%) of the total spent on private providers was spent on nightly paid, privately managed accommodation.4 The amount spent on this type of temporary accommodation has increased by 64% in the last year alone.

This increase reflects a shift from longer-term leasing of private sector accommodation to the charging of expensive nightly rates. The use of this type of accommodation now accounts for a quarter of all temporary accommodation. As a 2016 London Councils report suggests, the shift to the use of nightly rate accommodation has resulted in an increase in costs.

More investment in social housing is needed

Insecure, unsuitable, unregulated and expensive temporary accommodation is rapidly becoming the ‘new social housing’ – where the state accommodates those who are homeless because they can’t compete in the rental market. It’s also far from ‘temporary’ – with some families living in it for over a decade.

Instead of spending billions on such poor-quality accommodation, which can be incredibly damaging to children, we should be investing in genuinely affordable, decent, permanent and well-regulated social housing. This would achieve a levelling up of life chances for families who struggle with the cost of living crisis that continues to fuel our housing emergency.

Please join our campaign and call on the government to invest in a lasting solution to end the housing emergency by building social homes.

Footnotes:

1Households need to be in ‘priority need’ and eligible (due to immigration status) to be owed a temporary accommodation duty.

2This increases to £1.58 billion when temporary accommodation administration is included.

3Temporary accommodation provided directly by private landlords is not included in this figure as this is only published in an aggregated ‘other’ category.

4This only includes nightly paid accommodation that is self-contained. If nightly paid shared accommodation was included, the amount spent would be even higher.