The Benefit Cap: hamstringing housing associations?

Published: by Shelter

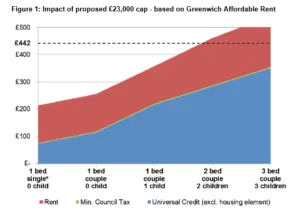

The government has confirmed that the Benefit Cap, which since April 2013 has limited the total benefits certain households can receive, will be lowered from £500 to £442 a week (£23,000 a year). We’ve already demonstrated how the lowering of the Benefit Cap is likely to impact on families’ ability to get and hold onto a tenancy in the private rented sector. But we’re also worried about the potential impact of the cap on those who rent social housing, including stock owned and managed by housing associations.

Last week National Housing Federation chief David Orr highlighted that lowering the Benefit Cap could affect an additional 37,000 current housing association households – and that’s not including those in council housing or temporary accommodation.

So what does this mean for housing associations?

The way the cap works is that the difference between a household’s total benefit entitlement and the £442 limit is taken out of their Housing Benefit (which is currently paid direct to housing associations). So housing associations are understandably worried that their existing tenants affected by the new cap will struggle to pay their rent, as few will be able to supplement the rent from other income.

This is not just a problem for those lucky enough to have an affordable tenancy already. The lower cap will also mean that large numbers of homeless, vulnerable and low paid households on the waiting lists will be unable to get an affordable tenancy in many parts of the country.

For example, research conducted by housing association Moat reveals that the lower cap level would severely limit people’s ability to get or maintain a social rented tenancy, and that this impact would be even worse for the new Affordable Rent tenancy (as these rents are set higher than social rents, at up to 80% of the private market rate). The research suggests that across the South East the new cap level would mean the amount of housing benefit that could be claimed would not cover the rent on three bedroom social rented homes, and that overtime two bedroom properties would also become unaffordable. Therefore, according to Moat’s research, only one bedroom properties would remain affordable to affected households with one or more children.

The graph below highlights how accommodation larger than a one bed in the social rented sector becomes unaffordable to households.

Source: Moat ‘Rent Levels and the Benefit Cap’ 2014

What is most alarming is that, contrary to some of the rhetoric surrounding the Benefit Cap, Moat’s modelling doesn’t cover more expensive inner London areas, but instead shows that social housing across most of the South East will eventually become unaffordable. And this isn’t just about large families either. For example, the chart below demonstrates that two bed properties in places such as Ashford, Dover and Basildon will eventually become unaffordable under the new cap.

Source: Moat ‘Rent Levels and the Benefit Cap’ 2014

And what are the consequences?

The impact of lowering the cap raises immediate concerns for affected households living in the social rented sector. But it also presents a very serious threat to the longer term supply of social and affordable rented accommodation. This threat is posed in three main ways:

Firstly, at a time when we desperately need to build more affordable homes, the lowering of the cap makes it harder for housing associations to develop new units. Moat’s modelling highlights the risks that tenants might not be able to pay the rent on two and three bedroom properties, so building more of such family sized homes would be a risky proposition for associations. The current cap level of £500 per week has already forced some housing associations to stop building three and four bedroom properties, prompting a call from the sector for the cap to be indexed to inflation to prevent this problem from spiralling.

Secondly, while housing associations once financed their new building with upfront government grants, cuts to these grants mean that they must now finance most of their building from debt, secured against future rental income. By undermining the ability of their tenants to pay the rent, the government is kicking away another leg of housing associations’ business model.

Finally, and perhaps most obviously, the cap will likely drive up rent arrears, and requiring associations to assist struggling tenants and therefore inflating housing associations’ management costs. This will further destabilise the sector and deter building, and means that more tenants will face eviction or falling into debt.

All this means that associations may be forced to cater only for those tenants unaffected by the cap, and to build fewer social and Affordable Rented properties in future. This can only worsen homelessness across the country.

The government urgently needs to ask itself: how can housing associations be expected to deliver new homes while suffering further cuts to capital grants, the forced sale of their properties, and the restriction of their rental income due to the benefit cap – all at the same time?

At a time when we need record numbers of houses to be built, hamstringing housing associations is helping to deepen the overall housing crisis.