The evolution of Starter Homes: from a useful addition to a serious threat

Published: by Toby Lloyd

When the government first announced plans to build 100,000 ‘Starter Homes’ a year ago, we welcomed the commitment to get more land released for building homes, and to use the value created to make these homes more affordable than the market otherwise would. We felt that building some homes for sale to first time buyers at a 20% discount on the market price could be a useful addition to overall supply – as long as this was actually additional supply and didn’t replace genuinely affordable homes in the process. So we hoped that the government would listen to our concerns and drop the idea that this new form of housing could be paid for by scrapping the requirements on developers to build genuinely affordable homes – known as Section 106 agreements.

The word ‘affordable’ is becoming increasingly confused, so to clarify, I’m using it in two ways here. In normal usage, a home is ‘affordable’ to a household if they can afford it – the rule of thumb being that rent and/or mortgage payments should cost no more than one third of their income. Clearly, whether a market home is ‘affordable’ or not depends on the household’s income, so the term can’t be applied to any specific home without reference to who’s getting it: even the most expensive homes are affordable to someone.

But there is also the technical planning policy term ‘Affordable Housing’, which refers to specific homes that are provided at below the market rate. Typically, Affordable Housing means social rented or shared ownership homes whose construction is subsidised in some way. Subsidy comes in two main forms: planning subsidy is effectively profit the developer is required to forego by building some Affordable Housing instead of market homes; grant subsidy is government cash paid to the developer. Affordable Housing should always be cheaper – and hence more affordable – than equivalent market homes.

One year on, and we now know a lot more about the Starter Homes proposal. Firstly the target has doubled to 200,000 Starter Homes this parliament. But we also now know that the government intends to change planning rules to count Starter Homes as Affordable Housing – which means they will in fact replace more genuinely affordable homes that might otherwise have been built. And following the Comprehensive Spending Review’s (welcome) announcement of an increase in the public subsidy going into house building from 2018, we also know that government grant will be given to developers to get them to build Starter Homes.

This means that developers will now be getting both planning subsidy and grant subsidy to build homes for private sale that are only slightly more affordable than those on the open market. And these homes will not even remain slightly more affordable for long: after five years the buyer can sell them at the full market price.

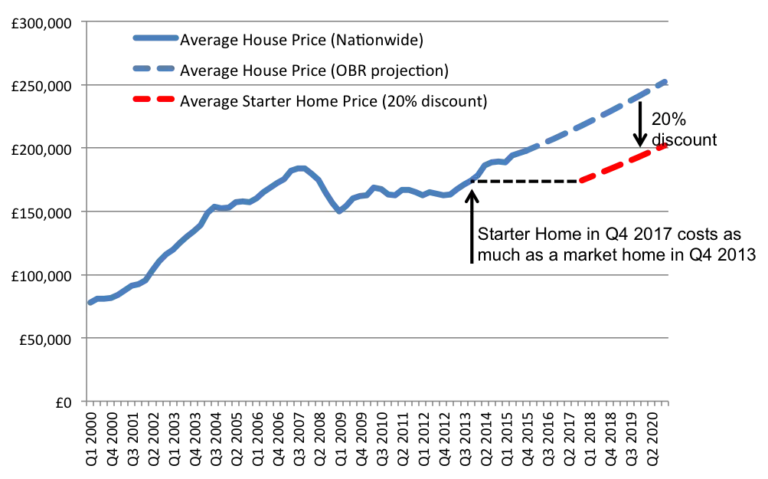

This might be good news for some on the margins of homeownership, but these Stater Homes will be out of reach for the majority of households struggling in our dysfunctional housing market. There’s also the small matter of what a 20% discount is really worth: the first Starter Homes are scheduled to be sold in 2017, by which time house prices in many parts of the country are expected to be more than 20% higher than they were when the initiative was announced. So all that subsidy will only allow first time buyers to get a home at the same price as it would have cost on the open market in late 2014 – which was sufficiently unaffordable to prompt the launch of the policy in the first place…

What’s really worrying is that Starter Homes will not only be built instead of new Affordable Housing in future, but will replace Affordable Housing in schemes that are already being built.

This change was announced in a letter from housing minister Brandon Lewis to local authorities in November, and published by Inside Housing. It’s described as a technical change to prevent the cut in social rents announced in the Budget from rendering existing planning permissions ‘unviable’. The issue is that lower social rents are undermining housing association’s business plans to the point where they may not be able to buy new Affordable Housing that developers have pledged to build under Section 106 planning obligations. Developers may then want to renegotiate these obligations – to reduce the amount of Affordable Housing that they have to built. The minister’s letter encourages local authorities to be ‘flexible’ in these renegotiations – and to not ask too many questions when developers seek to change Section 106 agreements.

Specifically, the letter suggests that if the developer proposes that the ‘tenure mix is adjusted, with the overall Affordable Housing contribution remaining the same’ then no formal renegotiation should be required, and the developer should be allowed to replace any homes pledged with ‘alternative forms of Affordable Housing.’ Assuming the definition of ‘Affordable Housing’ is changed to include Starter Homes, this will allow developers to replace promised low rent or shared ownership homes with Starter Homes – from as early as spring 2016.

In short, not only the future supply but the existing pipeline of Affordable Housing is likely to be cannibalised to provide Starter Homes. In one short year this policy has come a very long way from being a potentially useful addition to the supply of homes for first time buyers, to become a serious threat to the provision of any Affordable Housing.

We’ve said it before, but getting rid of Affordable Housing is no way to solve the affordability crisis.