The true cost of the Right to Buy

Published: by Pete Jefferys

If you’re a family searching for a home in Stevenage the chances are that you’ll need to rent from a private landlord. Shelter research in April found that there are no 2 bedroom homes on the market in Stevenage that a family earning the average income in the town could afford to buy, even if they already have a deposit saved up. So families searching for a home are likely to come across rented properties like this two bed on Garden Walk.

This home is in an area of Stevenage that was built early in the town’s development in the 1950s and 1960s – when all the homes built were for low council rents. However it isn’t available for families at those low rents any more. Like many of the homes sold under the Right to Buy in Stevenage this home is now a private rental: with a short term, insecure contract and much higher rents.

Whoever ends up renting the home on Garden Walk will be paying around twice as much as they would if it were still an affordable home (an extra £5,000 per year). For a family with kids on a normal income, that’s the difference between managing and struggling.

Research out today from Inside Housing showed that almost 40% of flats sold under the Right to Buy in England are now private rentals, while in Stevenage, Milton Keynes and Corby it is closer to 70%.

However it’s not just families in these towns that are losing out from the Right to Buy. Over the long term this policy is making the dream of home ownership more distant while costing taxpayers a fortune.

Right to Buy is five times as expensive as building new homes

We are not opposed to the Right to Buy in principle, as long as the homes sold are replaced like for like. However it’s hard to see that it is a good use of public money compared to other options to increase home ownership. For each two bed home in Stevenage that goes from social rent to private rent, this is what taxpayers can now easily end up paying:

- £60,000 to subsidise building the low rent home in the first place (NAO, 2008-2011).

- Plus £77,900 for the discount to the tenant to subsidise the sale under the revitalised Right to Buy.

- Plus £2,920 per year in housing benefit if it’s let to a family who qualify for support.*

Fifteen years after the home becomes privately rented, that represents a cost to taxpayers to build, transfer the tenure and then subsidise private rental income for that home of £181,700.

If the public sector spent that money more wisely it could build two new social rented homes (with a £60k subsidy each), plus build three new homes for shared ownership (with a £20k subsidy each) to help young families buy a home of their own.

We could get three new home owning families and two desperately needed rented homes for families on low incomes, rather than just one home that ends up private rented anyway.

And it is contributing to the slow death of home ownership

The Right to Buy is also rubbish at what it’s supposed to achieve – home ownership. While in the short term it provides a windfall to lucky renters who can cash in on the discounts, selling off affordable homes contributes heavily to the struggle faced by the next generation in buying their own home.

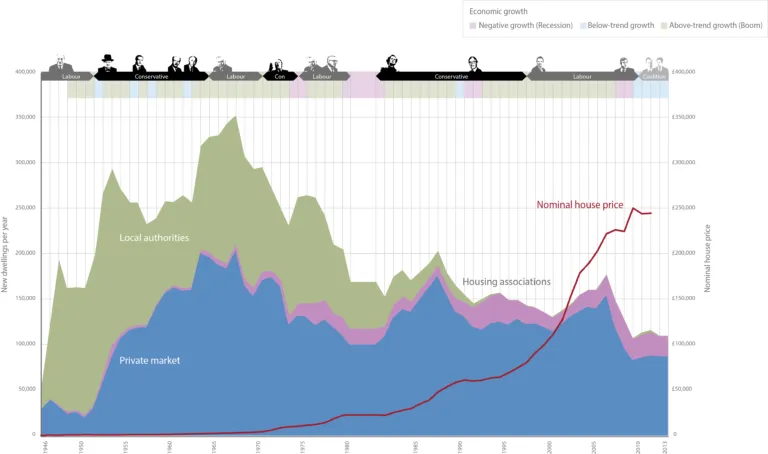

Since the Right to Buy was introduced in the early 1980s councils have fallen out of the business of building homes. The inability of the private market to fill the gap means that since that time, we’ve consistently not built enough homes. We’re now at the point where every year we build only half as many homes as we need to keep up with a growing and ageing population.

As we’ve seen today, 40% of the flats sold off end up as private rentals anyway rather than adding to owner occupation. It’s much harder to save a deposit when you’re renting privately – renters now spend on average 47% of their disposable income on their rent after housing benefit, compared to just 32% for social renters.

The collapse in housing supply is due to multiple factors no just the right to buy, but undoubtedly the change in the role of local authorities within housing – from active builders to simply managing a declining stock has been a key factor. We’ve never achieved the promise of building a replacement home for every one sold off: in fact for every 9 homes sold just 1 is built.

This doesn’t mean we have to go back to the old model and build 1960s style council housing though. Public bodies could play a different role to the past focused on land assembly rather than construction and management, for example. The role could be more like that played by the Olympic Delivery Authority in building the Olympic Park in Stratford: strategic planning, land assembly and partnership with the private sector.

It does mean though we must think very hard about the long term impacts of the last Right to Buy before we charge ahead and extend it to a million housing association homes. It may be that there’s a more cost effective solution to increase home ownership.

*This presumes that the council tenant buys after the qualifying period for the full subsidy and waits before letting it out. Annual Local Housing Allowance of £8,100 minus annual social rent of a 2 bed house in Stevenage of £5180 (to account for household fully supported on HB).