Time to look again at viability?

Published: by Catharine Banks

A joint report released last week by researchers at a group of universities has confirmed some long-running suspicions. We have noticed in recent years that some developers seem to have been taking advantage of planning policy to maximise their profits – and so increase the amount of money they can offer landowners in the competitive land-buying process. They can do this by arguing down the amount they’re required to contribute towards new affordable homes, infrastructure, and community facilities, in the negotiations they have with local authorities when they apply for planning permission. From evidence of individual schemes, we have long suspected that the balance of power in these negotiation has tilted excessively towards the developer, undermining the provision of desperately needed affordable homes. But this report confirms that aggressive practices are widespread in the industry, and looks at their impact on the provision of affordable housing in London.

So how does this process work? At its most simple, the value of a piece of land is the value of what you can use it for, minus the costs of that use. This is why land with residential planning permission is worth much more than land used for agriculture or industry. In the case of residential land, its value is calculated as the total value of the homes that could be built on it – what they could be sold or let for – minus the costs of building those homes, putting in the roads and utilities to support them, and a return for the developer. This method is known as residual land valuation. It’s part of what makes housebuilding so risky, because developers must guess how much they will be able to sell homes for, several years in advance, and then commit themselves to a land spend which reflects those estimates. If they get it right, and the total costs of development are projected to be less than the total value of what’s going to be built, the developer will make a profit, and the scheme is said to be ‘viable’.

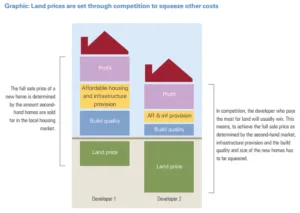

But a lot hangs on how ‘viability’ is defined: how much profit does a developer need to make for it to be worth their while to build the scheme? Where there are strong planning policies present, clearly setting out what infrastructure contributions will be required to support new homes, and the proportion of homes that should be affordable, developers will factor these contributions in as costs of development, and calculate the amount they can offer for the land accordingly. In effect, the cost of the contribution to the community comes off the price to the landowner.

However, since 2012, we haven’t had those strong planning policies in place to help set land values, because the definition of viability was changed. The NPPF states that:

To ensure viability, the costs of any requirements likely to be applied to development, such as requirements for affordable housing, standards, infrastructure contributions or other requirements should, when taking account of the normal cost of development and mitigation, provide competitive returns to a willing land owner and willing developer to enable the development to be deliverable. [emphasis our own]

The intention of this was essentially reasonable. Housebuilding had slumped in the wake of the recession, because house prices had fallen significantly below the levels which developers had been using to calculate their land bids. Schemes became ‘unviable’ as developers obviously didn’t want to make lower profits or even losses on schemes, so they stopped building altogether. Changing the definition of viability to be ‘competitive returns to a willing land owner and willing developer’ (rather than ‘reasonable returns’) gave developers the ability to argue for lower contributions in order to keep their profits up to ‘competitive’ levels.

However, once the housing market started to recover and developer profits rose, developers began to factor in this ability to negotiate down their planning obligations when calculating how much they could offer for new land bids. As with changes to space standards, any policy changes that affect development costs or returns are rapidly priced into the land market – and become the new default assumption. The result was that, even as prices and profits soared, the amount of affordable housing contributions fell. JRF research showed that in 2013–14, 16,193 homes in England were completed through S106 (37 per cent of all affordable homes) compared with over 32,000 in 2006–07 (65 per cent).

Taken from Shelter and KPMG, Building the homes we need, 2014, p34

Government have tried to tackle this by saying that developers can only have their planning obligations reduced on viability grounds where the developer has paid market value for the land, which should take planning obligations into account. But this takes a naïve view of the competitive manner in which market value is arrived at – as shown in the graphic above. If everyone assumes they will be able to build without complying with policy obligations, then everyone will start to pay an amount that would make policy level obligations unviable – and the market itself then settles at a price that makes policy level obligations unviable.

So the NPPF definition of viability that was intended to get development moving again became an intrinsic part of the land valuation and planning negotiation processes, undermining the system’s ability to secure affordable housing contributions. Getting homes built, and getting them built quickly, is of vital importance. But we should not be prioritising developer and landowner returns from new housebuilding at the expense of the affordable homes we so desperately need.

At the heart of this debate is an awkward question: how is it that we have reached a point where affordable housing is seen as a cost which can be squeezed, but developer and landowner returns are fixed and non-negotiable? Of course we shouldn’t expect developers to operate for no return at all. And landowners shouldn’t be compelled to give their land away for free. But both developers and landowners are doing very well out of this system – increasingly at the expense of families struggling to afford a home. Perhaps it’s time for Government to look again at the principles underpinning the viability process.