Trying to make sense of current social housing policy

Published: by John Bibby

Social housing policy has for a long time been muddled. But, the retrograde proposal to end permanent secure tenancies for council tenancies is just the latest example of policy that is not only muddled, but eating itself alive.

Let me explain what I mean.

It is completely legitimate to want public policies to do a number of different things. In fact, it’s desirable. For example, we want the NHS to respond to medical emergencies, and to prevent poor health from occurring in the first place, and to give palliative care to people who are dying.

It’s the same with social housing policy. It’s fine to want it to do a number of different things, such as providing:

- Emergency help for homeless households;

- A stable home for people on low incomes;

- A way for low income families to buy a home;

- Mixed income communities.

The big challenge with having such multiple objectives and a limited pot of resources has always been prioritising between them. But in broad terms, that’s what public policy is about: deciding that you want to do A and B and C – and that you’re going to put more resources into B than C, for example

The problem comes, though, when you want it to do A and not B, B and not C, and C and not A – when you want to do a number of things that all make sense on their own terms, but no sense in combination.

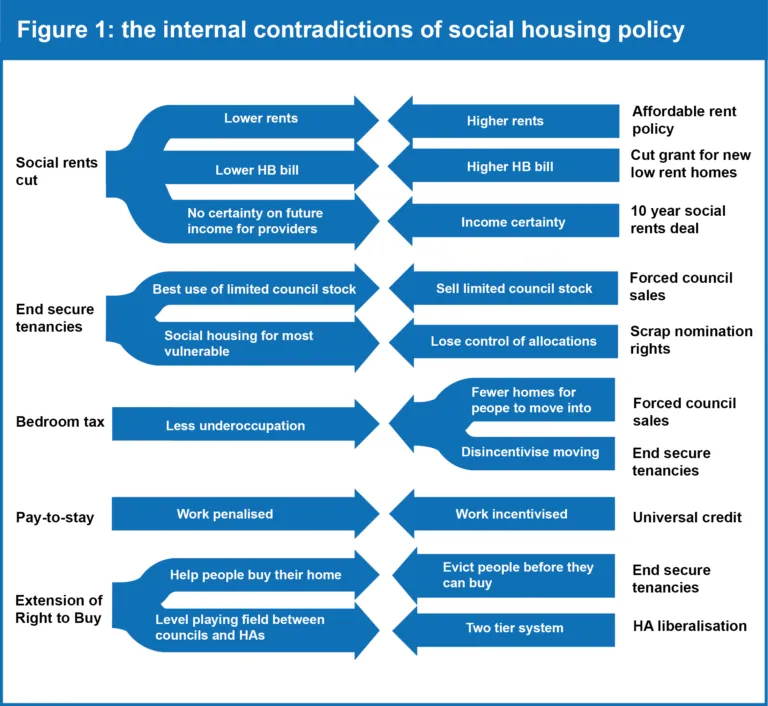

And this is the way social housing policy increasingly is: internally inconsistent and self-contradictory. This means that even with unlimited resources, the government’s agenda would still be running headlong into and undermining its own objectives.

I’ve made a stab at summarising some of the clearest current internal contradictions in social housing policy in Figure 1 below.

Perhaps the simplest example is the question of whether social rents should be going up or down – whether or not you think there should be a place for genuinely low rent housing. On the one hand we have the things pushing social rents up. These include switching new and existing homes from social rents to the new Affordable Rents, which was designed to make up for the 2010 cut in grant for new affordable homes by increasing the future rental income of housing providers. In effect this meant a switch in subsidy from upfront grants to increased ongoing payments through housing benefit.

Also on the ‘rents go up’ side we had the ten year deal agreed in 2013 to increase rents by more than inflation for a decade, which was supposed to give certainty to providers and their lenders, and put them in a strong position to build. We have the pay-to-stay policy to increase rents for households on incomes of more than £30k, which is justified in terms of the unfairness of higher income households getting cheap housing. Arguably, we also have the diversion of funding for new social rent homes and increasing reliance on the private rented sector for housing homeless households, for example.

But then, on the other side, sits the 1% annual cut to social rents announced in the summer. This was packaged as good for tenants and good for the housing benefit bill. It overrode some policies on the other side (notably the ten year deal) but still sits alongside others, like Affordable Rent conversion, which continues to load more onto housing benefit and pushes up rents for tenants. Also on this side, we have the decision not to oblige housing associations to implement pay-to-stay, so some ‘high income’ families in housing association homes will actually see their rent go down, not up.

We’ve been clear that we disagree with some of the individual decisions that make up this mixed bag of policies on their own terms, like the cut to grant for new social rented homes.

But there is further good reason to be concerned about the internal inconsistency between the policies themselves – and it’s not some misguided obsession with intellectual neatness. (Although having clear objectives does matter: if you create a system which requires impossible acts of mental contortion to understand, no one – not government officials, not local government, not housing associations, not tenants – will understand what’s expected of them, and they’re unlikely to implement policy effectively.)

The big danger of internally inconsistent policies is that instead of managing to do a bit of A and a bit of B and a bit of C, you fail to do any of them. This is not to say that you do nothing at all – that everything perfectly balances out – only that you do less than you could, that you do it less well than you could, and that you also do some unintended, undesirable things too.

In my view, the answer to untangling this mess is not to create some grand new singular vision of what social housing should be and how it should work. Public policy always has multiple objectives that need to be balanced within the context of scarce resources – and social housing is no different (although it could certainly do with more resource too). In my view, the answer is more pragmatic: be clear about your multiple objectives and don’t make them compete against one another in a way that makes them all harder to achieve.