We can’t keep banking on Mum and Dad

Published: by Shelter

It seems every day I read a story in the news about how difficult it is for first time buyers, earning decent salaries, to get that first foot on the property ladder. Recent research found that a couple with a child would be saving for 12 years before they could afford a deposit.

That means young people across the country trying to raise a family in insecure private rented accommodation, where every monthly rent payment feels like a wad of hard-earned cash down the drain – or else finding themselves back in their childhood bedrooms. More widely, it means a huge amount of downward pressure throughout the rest of the housing market.

With such repercussions, it’s no wonder that the phrase the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ has entered our lexicon in recent months. With the prospect of being able to afford a home of their own slipping away from so many young people, their parents are increasingly stepping in to lend a helping hand. In fact, it is now much the only game in town if you want to get on the property ladder – and 79% of England’s 9 million private renters do.

And parents have been helping out in droves. New analysis commissioned by Shelter has found that parents in the UK been gifting a whopping £1.2bn and lending £800m a year to homebuyers since 2005. Unsurprisingly, then, the Bank of Mum and Dad is now struggling –with parents dipping into their retirement savings and cutting back on their own spend to help their children. It is not a sustainable operation.

It’s hard to blame parents for wanting to help if they can. Most parents would do anything for their children, especially when so many managed to buy a decent size home themeselves with much more ease. The reality is that their children are working hard and saving, but feel like they are stuck on the renting treadmill.

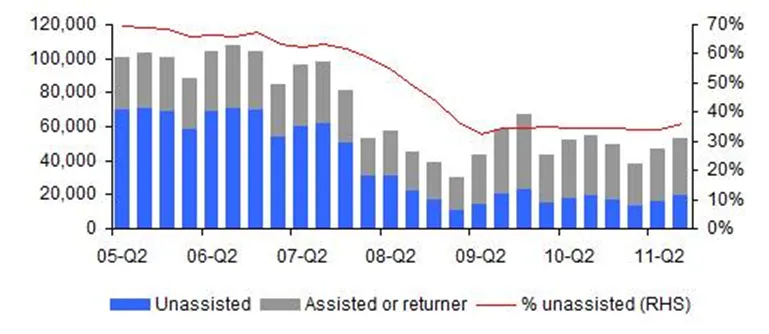

Financial support from parents has been a feature of the housing market for quite some time. 32,000 first time buyers were helped by their parents in Q3 2005, and 34,000 were in Q3 in 2011.

The big difference between 2005 and now is how difficult it is for people without parental assistance. 71,000 first time buyers bought a home without parental assistance in Q3 2005, compared to just 19,000 in Q3 in 2011. We’ve gone from less than a third of first time buyers getting parental help to almost two thirds.

It was to address this problem that the Government announced the headline-grabbing Help to Buy scheme in the 2013 budget, pledging to help up to 600,000 buyers get a low deposit mortgage. A shrewd move, perhaps, when you consider that all those private renters – whose hope of getting on the ladder is slipping away – look like a picture of the classic swing voter.

But the problem is that it’s not just big deposits that are holding people back from getting on the ladder, and politicians keen to boost homeownership for low and middle income families are going to have to look beyond this issue if they want to really tackle the problem. They need to start meeting people halfway – and a recent policy report by Shelter set out our thoughts on how government can do this.

The reason why politicians need to find a solution beyond Help to Buy is demonstrated by a further piece of Shelter analysis, due to be published shortly. It finds that even with the 95% mortgages possible through Help to Buy, the average family will only be able to buy a 2 bed home in 49% of the country, and lower quartile income families will only manage that in fewer than 1 in 5 areas.

Just reducing the deposit needed on a high house price means the buyer needs to pay a bigger mortgage. If those parents who are acting as the Bank of Mum and Dad already find it hard to raise the money to help with their child’s deposit, I’m not sure it will be any easier to help them pay expensive and ongoing mortgage costs.

Our forthcoming analysis suggests that much larger scale shared ownership schemes will bring the cost of buying a home and meeting housing costs within reach of many more hardworking low and middle income families. More government focus on schemes like this will likely meet the housing aspirations of a much bigger proportion of this key group of voters.