We must end one room living

Published: by Deborah Garvie

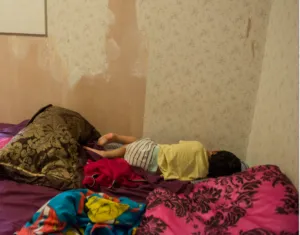

I recently visited Lorraine in the accommodation she shares with her two sons, aged 4 and 2. This consists of one 3 x 2 metre room, with shared cooking and bathing facilities. There is a double bed (which has to be directly underneath the second floor window), sofa-bed, fridge freezer, chest of drawers and a little table and stools for the children to eat.

When the sofa-bed is folded up, there is about 1sqm for the children to play, although they have few toys because there’s nowhere to keep them. In the winter, when it’s too cold to spend long in the local park, the children often hurt themselves bouncing around in the cramped space.

Lorraine and her family have spent 14 months in this tiny space, where every aspect of family life must be played out. Once the children are asleep, Lorraine spends her evenings sitting in the dark.

She’s desperate to move somewhere more suitable, which she could afford once her youngest starts nursery and she can get a part-time job. But the weeks and months pass, the children grow older and need more space. She bids for affordable social housing, but is never successful.

For Lorraine, moving to a cheaper town is not an option, because like many parents with young children, family support is what keeps her going. Her mum, sister and friends all live locally – she was born and raised in the area. The thought of being isolated with little money and no support is more dreadful than living in the room.

When asked for her message to people, she simply said ‘please help me’.

Such cramped family living is becoming more and more common – up and down the country, but especially in runaway housing markets like London. Distribution of living space is a growing issue. When single working people struggle to afford more than a partitioned off room in a run-down shared house, what hope is there for families like Lorraine’s?

Photo: Shelter

Shortly after my visit, I was at the Boundary Estate in East London as part of a university project on housing and well-being. The Boundary was England’s first council estate, built in the late 1890s on the site of the notorious Old Nichol slum, where poorly paid families, fearful of eviction, lived in one, cramped room. I thought of Lorraine when I was there.

The Boundary Estate came about because politicians felt an urgent need to improve the living conditions of the poorest families; there was public outcry because people were sleeping rough in Trafalgar Square. The Conservative Leader, Lord Salisbury, called for a Royal Commission, which resulted in the Housing of the Working Classes Act and the birth of well-designed municipal housing to replace the slums and improve the well-being of families.

This tradition of social housebuilding in expensive areas, where people would otherwise be forced into cramped conditions in the private market, continued throughout the 20th century. The emphasis was always on quality too: for example the 1961 Macmillan government introducing the Parker Morris space standards to future-proof new council homes.

The Coalition Government built on this tradition and, earlier this year, introduced the first set of national minimum space standards for all new homes, which can be applied by local planners ‘where this would not stop development’. The Government is now consulting on new measures to clamp down on landlords who ‘trap and cram vulnerable tenants in unsafe, overcrowded homes’ via the extension of licensing of Houses in Multiple Occupation and a minimum size for bedrooms in shared rental properties.

The introduction of minimum space standards is vital if we are to build more and better homes, and we’re delighted that the Government has taken this first important step.

The next step is to ensure that enough genuinely affordable homes are actually built at the new standards, where they are most desperately needed, so that families like Lorraine’s are no longer forced to live in one room.