The government’s ‘Right to Buy 2’ proposal is a complicated mongrel of a policy, combining two very different elements. The plan is to let tenants of housing associations buy their social homes, with the generous discounts of the Right to Buy, and to fund those discounts by forcing councils to sell their social homes on the open market.

It’s like something you could imagine being hacked together in Frankenstein’s workshop. So it’s not surprising that not many people outside the housing sector have fully got their heads around it yet. There’s a lot of confusion about which homes will be sold, who will end up owning them, what will get built, who will win and will lose.

In short, the policy is a case of robbing Peter to pay Paul. It’s giving housing association tenants in one place a windfall discount of up to £104,000 off the price of buying their home, and paying for it by having a fire sale on council homes somewhere else.

In more detail, it looks like the system will work like this.

It starts with the more expensive parts of each region in the country. Councils in these places are going to be forced to sell lots of their more valuable social homes, to the highest bidder. These homes aren’t going to be sold to social tenants, like under the Right to Buy, but on the open market to whoever will pay the most. By definition, these are relatively expensive homes, so no first time buyer is going to be able to afford to buy them either. They’re most likely to be bought by existing owners, investors and landlords.

Our analysis suggests that the places likely to lose most homes include: London, Leeds, Cambridge, Epping Forest, St Albans, Dacorum, Welwyn Hatfield, Warwick, Newcastle and York. In all these places, scarce low-rent council homes are going to be sold off to whoever can pay the most.

It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that, because these are the places where housing costs are highest, they’re also places that really need low rent council homes. Sure enough, in the top 20 council areas that we estimate are going to be forced to sell most homes, almost 160,000 households are currently waiting for a council home and over 22,000 children are homeless in temporary accommodation.

So this policy will force councils to sell homes that those families would have previously been able to move into. Many, if not all, of those families on the waiting list will have to keep renting privately – leaving them stuck with high rents and low security, and adding to pressure on the housing benefit bill. Ironically, many of them may find themselves renting the very properties sold by the councils, but paying far higher rents: we know that a large proportion of council homes sold so far have found their way in the hands of buy-to-let investors.

Now in some cases it might make sense to sell a really expensive council home if you’re going to be able to use the money raised to build a lot of new council homes nearby. Councils already do this, where it makes sense, on a case-by-case basis.

But the councils that are forced to sell homes won’t even get to keep the cash to build replacements: they will be forced to hand over the money to the Treasury. Almost all of that money is then going to go straight out of the Treasury again to fund Right to Buy discounts to housing association tenants.

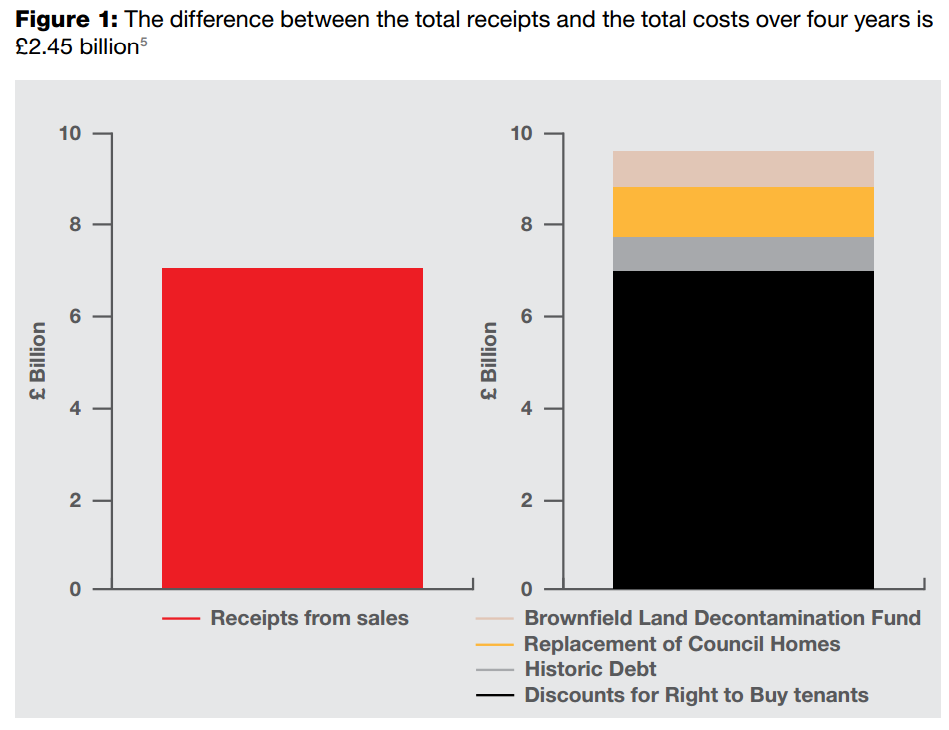

Funding those discounts is going to use up almost all the money raised by forcibly selling council homes, because the discounts offered are so big – and the government has promised to pay for them.[1] Housing association tenants will get up to £104,000 off the price of buying their home. Altogether, we estimate that paying for this will cost the government £7 billion over four years, while selling council homes will only bring in £7.2 billion.

The housing association tenants who benefit won’t necessarily live anywhere near the council homes that are sold. In fact, it’s likely that some parts of the country with a lot of housing association tenants are going to be subsidised by other expensive parts of the country with a lot of council homes.

And while the government is promising to replace all of the council homes that are sold, it isn’t promising to do that anywhere near where they were sold. It could mean selling a home in Warwick and ‘replacing’ it in Wakefield – with a smaller home, years later. (I’ll spend more time on what a good replacement scheme might look like in another post soon, or you can read our full report on it here.)

So this is why the policy is like robbing Peter to pay Paul. Housing association tenants in one place will get money off buying a home only by locking people on the housing waiting list somewhere else out of a social home.

Robbing Peter to pay Paul. In fact, it’s worse than that, as Paul is a housing association tenant with a secure, affordable home already – whereas Peter is homeless or struggling in the private rented sector, desperately hoping for a social home.

We don’t think that this is the right thing to do. We think that the government should be focussing on building more affordable homes, not selling off the ones we already have. That’s why we’ve called on them to scrap this scheme and put their energy into looking at how we can get more additional affordable homes built.

Join our campaign calling on the government to invest in affordable homes.

[1] There is a difference here between the original Right to Buy for council tenants and the Right to Buy for housing association tenants. The government didn’t have to find a stack of money to fund the big discounts for the Right to Buy for council tenants because the state already owned the homes. So the government was just able to tell councils that they had to sell council homes for less than they were worth. Housing associations are independent charities – so the government can’t do this.

But housing associations are independent charities. The state doesn’t own their homes. So it can’t just tell them to sell homes at a cut rate without fully compensating them. Otherwise, it’s just seizing private assets.