A report published yesterday suggests that the Right to Rent policy could be causing discrimination in the rental market. The government should use its upcoming private landlord survey to research whether its policy is leading to some unintended consequences.

It has been just over a year since a new law was rolled out in England to force landlords check their tenants’ immigration status. The Right to Rent scheme, part of the government’s multi-pronged approach to cracking down on illegal immigration, is a deliberate attempt to make life tough for migrants who are in the country illegally. And since December, landlords can face five years in prison for knowingly letting to someone who does not have the ‘Right to Rent’.

But while this scheme is aimed at deterring illegal immigrants from the rental market, worrying research yesterday concluded that many more renters could get caught up in its unintended consequences.

Passport Please, a report by the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, surveyed landlords, lettings agents and councils, and conducted ‘mystery shopping’ to understand the impact of the new policy. It found worrying discrimination against non-British citizens and found that nearly half of landlords are less likely to rent to someone without a British passport when considering the Right to Rent sanctions.

This study is yet more worrying evidence that has emerged highlighting discrimination in our rental market, fuelling concerns that the Right to Rent policy could make things worse.

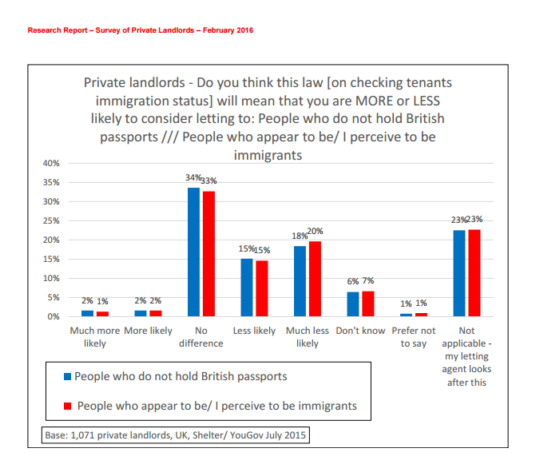

Troublingly, Shelter’s own survey of 1,000 private landlords has found that 37% thought it was “natural for prejudices and stereotypes to come into letting decisions”. What’s more, four in ten – 44% – of those making letting decisions said they were less likely to rent to people and families who ‘appear to be immigrants’ as a result of the Right to Rent scheme.

It is unlawful to discriminate against people from different racial backgrounds under the Equalities Act. Unfortunately, tenants are unlikely to know they have been discriminated against if the answer to their inquiry is simply “the room has gone”.

An investigation by the BBC in 2013 showed the disturbing ways that discrimination can occur under the radar, with one lettings manager allegedly saying: “We cannot be shown discriminating against a community. But obviously we’ve got our ways around that.”

So how are ministers monitoring the effect of the Right to Rent and whether it is presenting additional barriers to those from different ethnic backgrounds? A government evaluation of the Right to Rent pilot could not identify instances of discriminatory behaviour. But it admitted that its tenant survey and focus groups were dominated by students, who are seen as relatively easy to check.

Although Shelter is part of a consultative panel to monitor the scheme, the government has not revealed any ongoing data collection to do with the policy.

We understand the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) is preparing to launch a new survey of private landlords. Its last private landlord survey was in 2010 and the rental market has changed considerably since.

This new survey could represent a prime opportunity for the government to monitor the impact of the Right to Rent. If landlords are flouting the law and discriminating against certain groups, then now is the chance to find out.

On the other hand, if the government wishes to claim that the Right to Rent has had no discriminatory impact, then now is the opportunity to prove it.