How we improved our helpline to reach more people in urgent need

Published: by Matteo Remondini

The housing enquiries people come to us with vary from minor landlord disputes, to homeless families facing a night on the streets. That’s why we decided to examine how we could make sure our housing advisers help callers to our helpline who are in the most urgent need.

This also gave us the opportunity to see how we could improve our self-help services – like our advice webpages – for users who don’t necessarily need to speak to an expert adviser.

Identifying the problem

Our research showed us that we were categorising ‘emergency’ situations from a legal perspective – without considering the individual situations and feelings of people who came to us for help.

For example, we came across many examples of people who called our helpline because they were struggling with housing problems which would typically be considered as non-urgent or easy-to-solve issues. But due to personal circumstances, like learning difficulties or issues with mental health, the callers saw their problem as much bigger, more urgent issues. This meant they needed to speak with an adviser directly.

A new way to categorise calls

To address this, we began working with the Telephone and Online Advice Services team, and our helpline advisers to come up with a new list of criteria to help us assess the urgency of calls received.

We decided a caller’s situation would be classed as an ‘emergency’ when a person:

- feels extremely overwhelmed about their housing situation

- has nowhere to sleep, or might be homeless soon

- has somewhere to sleep, but nowhere to call home

- is or could be at risk of harm

This helped us be mindful of the impact housing problems can have in individual situations, rather than just focusing on legal definitions. And we knew we could adjust any policies that might risk excluding people who fall outside of the legal definitions.

We then looked at a week’s worth of data from our helpline advisers to help us understand the kind of calls we were currently answering. We found that only around 23% of the calls answered by our helpline advisers were deemed ‘emergency’ situations by our new criteria. This gave us a baseline metric we could use in future testing.

We also looked at other situations in which a person might be a priority for help, and found the two most common solutions to our problem. Firstly, we considered the emergency services, who rely on their call handlers to triage patients and decide their level of need. Secondly, we considered public situations – such as priority seating on the Tube, or spaces in a car park – where it’s the individual’s responsibility to decide if they consider themselves in need of these priority resources.

Introducing the emergency helpline

As part of the ‘Get Help’ page launch, we ran an experiment where we would have a dedicated emergency line to the helpline. This number would take callers to the front of the helpline queue, and the first available adviser would then pick up the call. This would give people with urgent issues priority over other callers.

We published the number on our helpline page, along with clear guidance on what would be considered an emergency, so users understood when they could call this number. Over two months, we ran two different versions of our experiment; applying our learnings from the first, to the second.

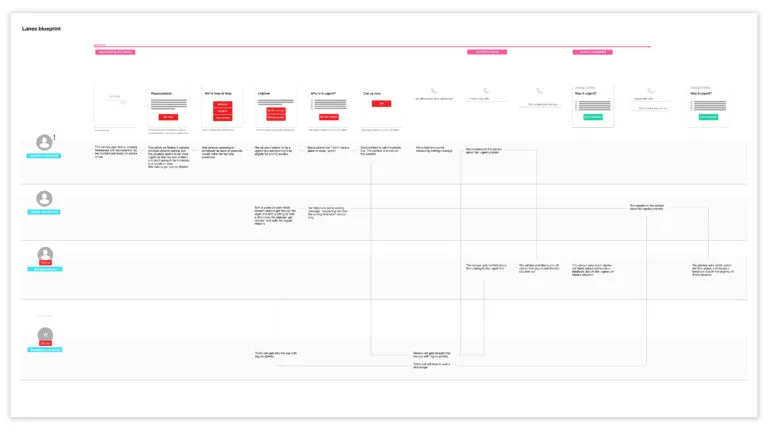

Blueprint map describing the feedback mechanism of the emergency helpline – click on the image to expand

Our impact

After another two months went by, we collected and analysed new data from our helpline advisers. We found that:

- around 25.5% of the calls we served were by people in urgent need of our help (an increase of 2.5% from the initial 23%)

- callers who felt they should be put through to an adviser as a priority call were three times more likely to have their call answered

- the second-most common reason callers needed emergency help was that they simply felt overwhelmed by their housing situation – showing our updated ‘emergency’ criteria really made an impact

Although we faced challenges during this project, including how to stop people from using the emergency helpline to unfairly skip the queue, we continued to learn from it. Ongoing data helped us keep shaping and improving the service – thanks to our partnership with our Telephone and Online Advice Services team.

Read all about the latest version of our emergency helpline – where we doubled the number of emergency calls we served – in the second part of this blog.