Rents continue to grind upwards. Incomes are being left behind.

Published: by John Bibby

It’s now a year since the Office for National Statistics overhauled their experimental rent index and it’s fair to say they feel pretty well bedded in. We now have what feels like a reliable measure of rent inflation, which had previously been a gaping absence in the statistical toolbox.

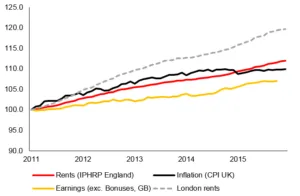

But while the fact of the index is cause for celebration, what it shows is anything but. In the last five years rents across England have outstripped general inflation and earnings growth – and in the capital they’re almost 20% higher than they were at the start of 2011.

Figure 1: Rents and earnings growth and inflation over the last 5 years

The ONS’s rent index (snazzily titled the Index of Private Housing Rental Prices or IPHRP) tends to be a pretty ‘boring’ statistical release in media terms, because unlike some other rent indices it doesn’t turn up eye-grabbing double digit rent rises or falls. It tends to move slowly up and down. This is mostly because it doesn’t track changes in market rents (i.e. what I would have to pay if I were to go and look for a new rent home today) but to track changes in average paid rents (i.e. what everyone who is living in rented accommodation actually shells out). So there is a lot of drag in the data resulting from people who agreed their rents months or years ago, meaning this particular data series is unlikely to ever be a block-buster. There’s more on that here, if you are interested.

In that context, the 2.7% annual rise in rents that the ONS chalked-up in the last three months of 2015 is strong growth. The 3.9% that was registered in London is really very high.

The last government made quite a lot of comparisons between rent growth and general inflation (the Consumer Price Index). It’s a comparison that makes some sense in media terms, because you get to say real-terms ‘rent cut’, if rents have moved up more slowly than inflation. The relationship between rents and inflation does matter, because many benefits are now directly or nominally linked to CPI inflation: so inflation-busting rent increases can mean benefits don’t keep up.

But apart from this indirect link via benefit uprating, general inflation is not a particularly useful comparison for rents. It doesn’t matter that much if rents have gone up in price more than Mars bars or toilet cleaner, for example. What we should really care about is how rent changes affect people’s ability to pay, and this is most affected by the relationship between their rent and their income.

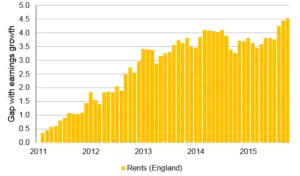

Unfortunately, when we compare rents with incomes, the news has been bad and getting worse for some time. The most readily available data source on incomes is the ONS’s Labour Market statistics, which show changes in earnings for Great Britain. These show earnings, excluding bonuses, growing pretty consistently more slowly than rents since early 2011. Rents are now 4.5% higher relative to earnings than they were five years ago, meaning that they have gobbled up more of renting households’ pay.

Figure 2: the growing gap between rent inflation and earnings growth over the last 5 years

Of course, there is more to household incomes than earnings. They don’t include welfare payments like tax credits, the state pension and housing benefit, or other payments like private pensions. But many of these payments have also been under considerable and sustained pressure over this period, particularly for younger households who are more likely to privately rent and haven’t benefited from the protection that’s been given to pensions.

In light of all this, the freeze on Local Housing Allowance rates is very worrying. Renters, even in working households, are already under pressure after years of income-busting rent increases. The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors have warned that rents could increase 5% annually over the coming years. And while past rent growth doesn’t mean that they will carry on growing into the future, the fact that rents have marched up in spite of tightening ability to pay is clearly observable. Without taking action to make sure that renters are able to keep up with rising rents, more and more will be driven into debt or forced to cut back on essentials like food and heating.