Why ‘internal transfers’ must be exempted from the forced council sales policy

Published: by John Bibby

We have previously detailed our concerns about the government’s proposal to force councils to sell low rent homes on the open market. I’ve summarised them here. In short, we think that it could inadvertently push up housing waiting lists, leave people in temporary accommodation, cut down new council house building, and more. Ideally, we think the proposal should be dropped entirely. But we also recognise that the government has committed to it and would therefore like to see protections in the Housing and Planning Bill so that these risks are mitigated.

One of the most important of those protections is the need to exclude homes that become vacant as a result of an ‘internal transfer’, so that these homes don’t have to be sold. Unless they are excluded then:

- councils may have a new perverse incentive to not help people to transfer to a more suitable home, even if they need to

- councils risk being faced with bills that they can’t pay

I’ll get on to why these two things will happen in a moment, but first: some background on what internal transfers actually are.

Internal transfers are vacancies that occur because the people who used to live in the council home have moved to another home within the very same council’s stock of homes.

There are lots of good reasons why people living in council housing might need to move to another low rent home. They might:

- Have found a job somewhere they can’t commute to from their current home

- Be ‘under-occupying’ their home and subject to the bedroom tax

- Be living in overcrowded conditions and need more space

- Have been moved out of a home that is going to be rebuilt as part of a regeneration scheme

- Have developed mobility problems and need to move to specialist housing or a place on the ground floor

- Need to be closer to relatives in their old age

Surprisingly, internal transfers account for 28% of all council house vacancies, and a further 7% of vacancies are where the occupier has moved to another social landlord.

But it’s inevitable that any new obligation for councils to sell homes that become vacant will reduce the number of internal transfers that occur.

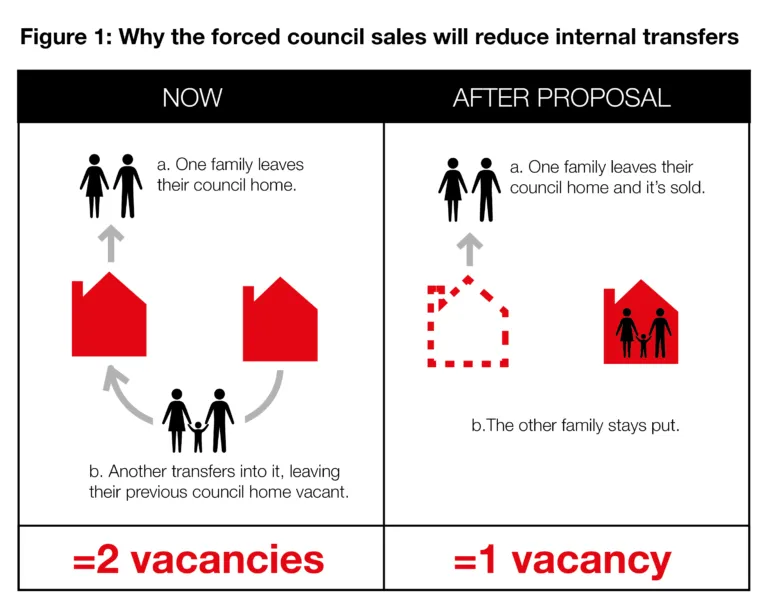

Think about it: if vacant homes are sold off, there will be fewer homes for people to move into. If a tenant who wants to transfer home doesn’t have anywhere to move to, they simply won’t move. I’ve spelled this out explicitly in the diagram below.

Given all the good reasons for encouraging internal transfers, this is a bad thing in and of itself.

However, if internal transfer properties are not excluded from the duty to sell then it could be even worse.

A perverse incentive not to help people transfer home

From the very beginning we’ve been worried that the forced council house sales policy might give councils perverse incentives – either to do undesirable things or not to do desirable things. For example, why would councils renovate homes if by doing so they would increase their values and make them subject to sale? Why would they build new council homes if they would just be forced to sell them off again, with the government taking the sale receipt?

Given that councils are the ones who agree internal transfers, there is an obvious risk that – unless they are exempt – councils are going to have a substantial reason to suppress the number of internal transfers that they approve even further. Why would a council help someone to move home if by doing so they would be forced to sell the home that’s become vacant?

So there is a risk that the existing drop in internal transfers will be made even worse. This would mean that national stock of council homes would be used even less efficiently and more people would find it difficult to move, even if they needed to.

Councils facing bills they can’t pay

The second reason internal transfers need to be excluded from the forced sales policy is because the specific way the policy will be implemented.

As I said earlier on, the forced sales policy will inevitably lower the number of internal transfers that occur and therefore the number of homes that become vacant even if internal transfers aren’t excluded. This wouldn’t pose any financial risk if councils were only going to be asked to hand over money for the homes that they’ve actually sold. But they’re not – they’re going to be asked to make a lump sum payment, up-front, based on the number of homes that became vacant in recent years.

So if the government fails to take into account the predictable drop in the number of vacancies that will occur, then their calculation will come out too high. Cash-strapped councils will be forced to hand over money that they don’t have and aren’t going to get without any chance to appeal (because that’s not in the bill either).

Everyone agrees that internal transfers are generally a good thing. Fewer of them will mean more people living in overcrowded conditions and less opportunity for council tenants to move to get work. It would mean fewer people moving out of homes that are too big for them or near family members who might care for them when they become old.

As such, excluding them from the policy – making sure they’re not suppressed even further and councils aren’t handed unpayable bills – is about as sensible suggestion as they come.